★★☆☆☆ | Nicholas Ntaganda, Contributor

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that Malcolm and Marie, one of the first Hollywood movies to be conceived and produced entirely during the COVID-19 pandemic, conveniently makes use of the conditions the virus has wrought upon the world.

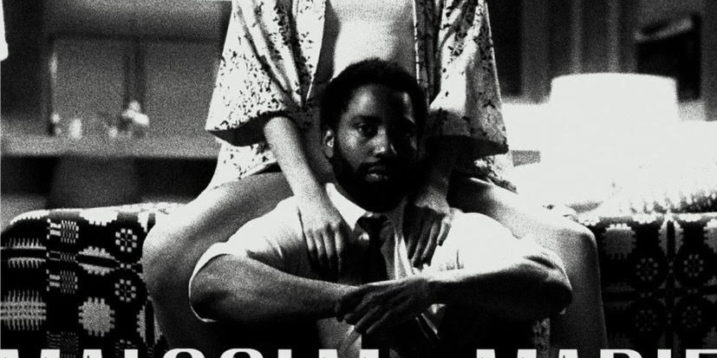

The film is a spare chamber piece/two-hander, with stars Zendaya and John David Washington being the film’s only credited actors. This domestic drama, which is the latest effort from Euphoria creator Sam Levinson, begins with the eponymous couple returning home after a movie premiere. Malcolm has just debuted his first feature film, which seems primed for critical success, but inevitably the tensions between the filmmaker and his would-be actor girlfriend rise to the surface, leading to what is essentially a feature length fight, punctuated occasionally by moments of affection and tenderness.

The film seemingly owes a great debt to Mike Nichols’ adaptation of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf; not only do they share a sadomasochistic streak and utilize only a single location, but both films are also structured like a boxing match, in which the lovers take turns delivering crushing blows to each other, then silently retire to other parts of the home between rounds before returning to continue the fight. The couple at the center of the brawl, however, are far less compelling than they should be for this structure to be successful.

Washington is easily the most egregious of the two; his performance is all exterior, his movements and gestures so obviously planned and rehearsed that there’s hardly anything left; no life, no spontaneity, no mystery. Just when it looks like the film couldn’t possibly be any more gruelling, Washington’s determined overreacting somehow makes the experience doubly exhausting.

Zendaya, for her part, is significantly better, although her performance still suffers because of Levinson’s mannered script, which supplies her (and Washington for that matter) with stiff, writerly dialogue that would surely be a challenge for even the most skilled performers to deliver convincingly. The screenplay also dedicates so much of its runtime to Malcolm, an obvious Levinson stand-in, and his endless ramblings on the state of film culture (“nobody cares about film anymore!”, he proclaims), that it becomes very hard to view the film as self-criticism and not as an exercise in solipsism and pretension. Though this might be unfair, the parallels between Malcolm and Levinson himself are so explicit that it becomes easy to conflate the two, especially once the former starts spouting off about movie critics.

One can’t help but feel that Levinson is only using a black character to legitimize his own views on identity politics in film criticism. But then again, the ways our artistic lives and our personal lives inform each other and become indistinguishable seems to be one of the film’s chief concerns; just as a viewer might be unable to discern Malcolm from Levinson, Marie wonders where she ends and the protagonist of Malcolm’s film begins.

Similarly, the characters are constantly arguing about how much of their behaviour can be attributed to artifice: does Malcolm’s relationship with his lead actor exceed professional boundaries or is he acting so friendly because he feels it’s part of his job? Has this actor lifted her acclaimed walk from Marie or is it her own invention? In short, the film is all about performance, which is why the two leads are constantly framed within frames, whether they be doorways or large windows, always giving the impression of being trapped inside a screen, a movie within the movie.

That propensity for artifice, however, doesn’t excuse how unconvincing the central relationship is. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf was also fascinated with performance, but underneath the cruel and hurtful words, one could see how this couple were once madly in love, partly because their brief moments of affection felt like the natural result of excellent chemistry and not an obligatory tonal shift. Even when Levinson’s performers seem to approach something resembling good chemistry, as they do during their intimate and lighthearted discussion about race, commercial cinema and Legos, Levinson can’t help but muffle the scene with a clumsy music cue and overactive editing, resulting in something more affected than affecting. That montage is an excellent microcosm of the entire film; there are moments of life here and there, but the entire exercise is so self-obsessed that it becomes harder and harder to care if that’s the point.

Malcolm and Marie was released on Netflix on February 5th.

Nicholas Ntaganda is a second-year student who is working to complete a double major in Business Administration and Rhetoric and Media. A native Sudburian, his great passions include impromptu musical numbers, crying during the happy parts in movies and bad transatlantic accents. For a more comprehensive (and less refined) look at his movie-watching, click here.